|

| Home | About us | Mod 2021 | Syllabus/Results | Gallery | Contact us |

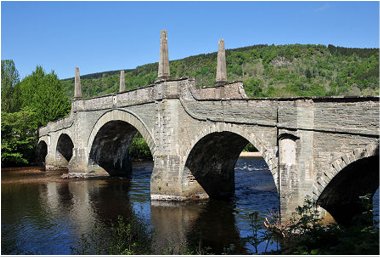

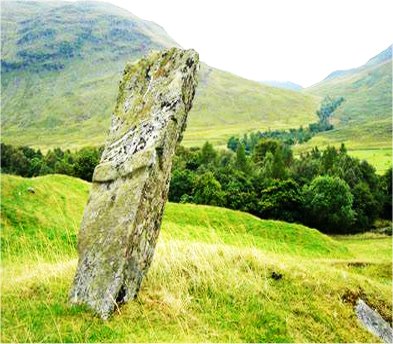

Read: The Aberfeldy Mòd – a Welcome for our Online Visitors Read: Why Write – a short biography by author Graham Cooper After leaving university, I began having articles published in surgical journals – the first one in 1981. There was a compelling reason to do this – I had been told that having a portfolio of published work would make me more likely to be successful in my career. And so, over the years, I produced a series of publications on a range of general surgical topics, all of which had to ‘run the gauntlet’ of reviewers and editors.  When I retired from surgery, I began to study the Gaelic language both from grammar books and at classes run by Aberdeen Gaelic Club. With the help of some excellent teachers, I seemed to pick the language up quickly. In 2016, I self-published a collection of brief homilies, ‘The Armour of Light’. At the same time, I was enjoying writing short pieces of fiction and non-fiction for a distance learning course at Sabhal Mòr Ostaig, the Gaelic college in Skye. Encouraged by my teacher in Aberdeen, I submitted a short story to the literature competition of the 2017 National Mòd in Fort William – it won the Donald MacIver Memorial Prize. This gave me the confidence to write my first novel, Dà Shamhradh ann an Raineach (‘Two Summers in Rannoch’), a story based on the life of Dugald Buchanan, a highly respected Perthshire poet and Bible translator of the 18th century. In the novel, I explored the themes of forgiveness and of steadfastness in the faith after tragic personal loss. The novel was short listed for ‘Best Fiction’ in the Scottish Gaelic Literature Awards of 2020.  My second novel, published in the summer of this year, An Ròs a Leigheas, (‘The Rose that Heals’), describes the pilgrimage to Tain made by King James the Fourth of Scotland a week or two before his disastrous defeat at Flodden in 1513. King James suffered greatly from a sense of guilt concerning his own father’s death – he had stood against him on the field of battle. So, in my second novel, the king’s unresolved guilt is a recurring theme. The backstory of another of the major characters, Master Henry Leich – one of a long line of hereditary royal physicians – shows his strong personal qualities of faith, loyalty, and dedication to the healing arts. The use of oil of roses as a salve for wounds and the significance of the rose in medieval Christianity together give the book its title. So, ‘Why write?’ Writing has given me the opportunities both to support the Gaelic language and to ‘let out the bats’ – to deal, in the context of fiction, with aspects of human nature that have interested me and perplexed me throughout my adult life. There are some thought-provoking blogs and short stories in English on criomagan.com Graham Cooper Books available to purchase at https://www.gaelicbooks.org If you are reading this you will probably already know that in order not to be defeated by Covid the Perthshire and Angus Provincial Mòd, which has met annually in Aberfeldy since 1923, has decided this year to go online. One of great bonuses for our Mòd must surely be its location in the beautiful Breadalbane countryside. For those of you taking part this year who will not be able to be here in person, the Aberfeldy Mòd Committee would like to offer a few sketches to provide some background colour to Bràghad Albainn and its place within the history of Gaelic Scotland. The origins of Aberfeldy emerge from the depths of pre-history as we can see from Oba(i)r Pheallaidh, its name in Gaelic. Oba(i)r is generally understood to have come into Gaelic as a loan word from the ancient Brittonic language, and in the form of ‘Aber’ is frequently found in place names in both Scotland and Wales. Along with its Gaelic equivalent inbhir, the word is usually associated with the mouth of a river or a confluence of waters. The aptness of the first part of the name becomes clear enough when you walk along the Moness Burn as it bubbles its way through the famous Birks of Aberfeldy before finally merging into the River Tay, but who we might ask was Peallaidh? The frontispiece of Edward Dwelly’s magnificent 1902 Gaelic dictionary states that it ‘contains every Gaelic word in all the Dictionaries hitherto published’ and so an extended entry under ùruisg does not disappoint. It explains that an ùruisg is ‘a being supposed to haunt lonely and sequestered places, a water-god’ and it seem that Peallaidh was one such. Although a common feature of Highland folklore, belief in ùruisgean was apparently strong in Perthshire. Dwelly explains that an ùruisg required little more than some kindly attention, so a seat would often be left for their use by the side of the kitchen fire but on the other hand, with disrespectful treatment an ùruisg could quickly turn to mischief. John Gregorson Campbell’s 1902 Superstitions of the Highlands and Islands of Scotland talks of the brùnaidh or ‘brownie’ and Dwelly, writing at this same time, tells of one such ‘brownie’ still believed to haunt a large house just across the river from Aberfeldy, earning for it the local name of Seòmar Bhrùnaidh (Brownie’s Room). Perhaps the peaceful silence in recent years of this noted brunaidh is due to its contentment at now having the creator of Hogwarts for an esteemed neighbour! Aberfeldy in its present size and importance did not really exist until the 18th century, indeed the establishment of the present community belongs to the creation of General Wade’s magnificent bridge (1) across the Tay making Aberfeldy into a strategic crossroad.  The bridge was built in 1733 to the design of the well-known Scottish architect William Adam however nowadays, it is more generally known by the name of its client rather than its designer. This is due to it being one of some forty bridges forming part of a 250-mile network of new roads built under Wade’s supervision in the aftermath of the failed 1715 Jacobite rebellion. It would be historically simplistic to say that the Jacobite risings represented Gaelic Scotland versus the rest of Britain, but the brutal suppression of Gaelic culture by the Duke of Cumberland in the aftermath of the Battle of Culloden can make it look a bit that way. Wade’s bridge formed the architectural jewel in the crown of an extensive military network designed to facilitate the rapid movement of troops to control disobedient Highlanders. It is then surely an irony that the first ‘military’ users of the bridge turned out to be Prince Charlie’s Jacobite clansmen who poured over the bridge on their way to the capture of Edinburgh in 1745! It can readily be seen that without its bridge Aberfeldy had little significance, largely because the principal road at that time passed along the north side of the Tay through Weem which is now joined to Aberfeldy by Wade’s bridge. It was not always so. Weem was established with its own Castle and a Church long before its now larger neighbour and has its own Gaelic roots as evidenced in its name.  The Castle Gaelic speakers will readily understand how the original Gaelic Uaimh (‘of a cave’) came in time to be misrepresented by Anglophone map makers as Weem, and it is this cave that points to Weem’s antiquity. The cave with its natural spring is halfway up the wooded rock behind the present settlement and can still be visited.  A strong tradition holds that this is the cave (3) where St Cuthbert retired in the 7th Century in order to spend time as a hermit. Cuthbert himself came from Melrose and subsequently became better known to history as the Abbot of the famous Lindisfarne monastery in Northumberland. It is suggested that the association of the well with St Cuthbert is only part of its story, being perhaps an adoption of an earlier site belonging to a culture which regarded natural springs as sacred. Anyway, Cuthbert could hardly have chosen a more agreeable spot, and for any future Covid free Mòd the cave offers a wonderful excursion with the added potential for refreshment afterwards in one of Weem’s two hotels. Of these, the Weem Hotel alongside the house where General Wade lodged, is said to be one of the oldest hostels in Scotland that has been in continual use as such. It is currently undergoing extensive renovation and will soon again be open. It is pictured below.  Just along the road, there is another ancient community which in local tradition is associated with another Celtic saint. St Adomnan became an Abbot of Iona following on from Columba, who came from Ireland bringing Christianity to Scotland along with our Gaelic language. Bede’s 8th Century account names Adomnan as taking part in the disputes between the English and Celtic Churches at the Synod of Whitby and differing accounts have him buried in either Ireland or Iona. However, a strong Breadalbane tradition tells a different story. One version of this has him being sent to evangelise the Scottish mainland, whilst another has him being expelled from Iona for having sided overmuch with the English clergy at the Synod of Whitby. Both traditions, however, have him ending his days in Breadalbane. As with much early medieval history the lines between fact and mythology become blurred but an alleged miracle attributed to Adomnan has a strange echo for our present times. The story goes that after his arrival there was an outbreak of plague in Glen Lyon. Various accounts tell how Adomnán summoned the community together and that he drew the evil plague energy into himself before turning around and expelling it into a hole in a nearby rock. However, to be doubly sure, he followed what would now certainly be recognised as good practice, by advising the community to move temporarily to a place known to be free from the disease. Upon their return the people were said to have erected the stone that later became known as Creag-diannaidh (5) – the ‘rock of safety’, as pictured here. Adomnan’s exploits were of course recorded under Eonan, his Gaelic name, which still appears on local maps at Milton Eonan, Eilean Eonain and Lageonan.  As we hope these notes make clear, one does not have to dig far to expose the Gaelic roots of Breadalbane. As our ancient language slowly slipped from community use during the 20th Century, it is impossible to overstate the important role played by of the Gaelic choir, the Aberfeldy Mòd and the Gaelic Playgroup in keeping those traditions alive to await the arrival of new speakers. We are pleased to report that things are beginning to look up. At Breadalbane Academy we now have a Gaelic Medium Unit in the Primary School with Gaelic also being offered at secondary level, living up to the Academy’s motto of Daonnan ri sàr-gniomh. Covid has certainly brought unexpected changes to all our worlds, and it can seem strange that this year it will be down to 21st Century technology to keep the venerable Mòd traditions alive by going online. We are of course looking forward to everyone coming back to Breadalbane in as soon as life returns to normal, but in the meantime, the Committee wishes to extend a warm welcome all those taking part in what promises to be an exciting new venture for us all. |